Sort by:

Hanky Panky: An Abridged History of the Hanky Code

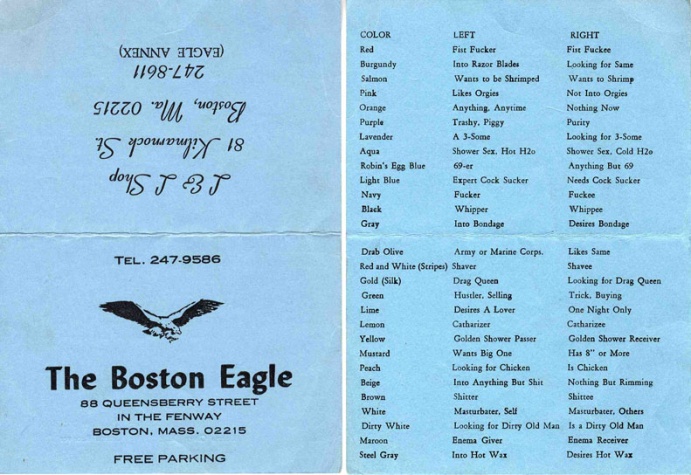

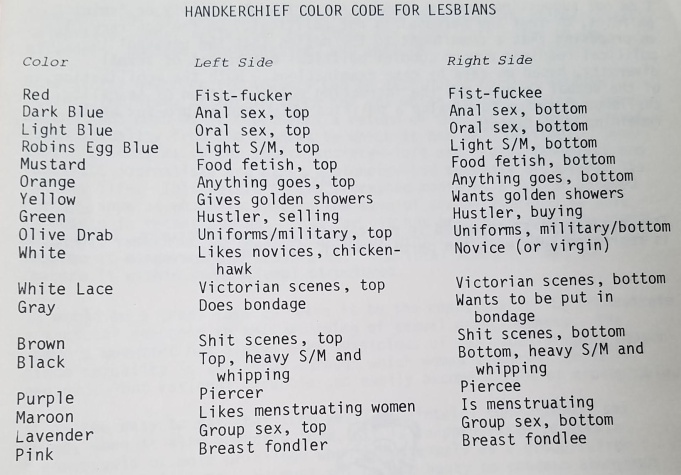

The hanky code was a covert sartorial code used predominately by queer men in the 1970s and into the 1980s. Simply put, a bandana is worn in one’s back pocket for the purposes of sexual signaling. The color of the bandana was associated with a specific sexual practice or fetish, and the wearer’s sexual role was indicated by which back pocket the bandana resided in (tops wore bandanas in their left pocket; bottoms wore bandanas in their right pocket). The hanky code initially began with the use of red bandanas to discreetly identify practitioners of fisting. A decoder list was created as other color/fetish associations were added. (In many early hanky codes, red typically appears as the first color.) Queer businesses printed the hanky code decoder lists for distribution. Erotica shops, bookstores, and catalogs provided decoder lists with the purchase of bandanas, while gay bars printed the lists with location information as a form of marketing. The origin of the hanky code exists like myth or urban legend, with two or three main stories surrounded by a variety of altered details, depending on the source.

Use of the hanky code spread throughout the mid 1970s. Practiced predominately by queer men in the Bondage, Discipline, and Sado-Masochism (BDSM) or leather subculture, the hanky code became part of the gay mainstream. From magazine article illustrations to book covers, images of a bandana tucked in a denim back-pocket became a visual shorthand for queer men. Additionally, terms such as hanky code and flagging (the act of participating in the hanky code) became part of the queer lexicon. As a part of queer popular culture, references to the hanky code eventually appeared in literature, film, and art. These developments not only documented the once underground phenomenon, but created a cultural record of an emerging queer masculine identity. These cultural references have continued through the decades.

A decrease in the use of the hanky code in the mid-1980s has been attributed to the curbing of anonymous sexual practices in relation to the rise of HIV/AIDS. However, hanky code flagging continued in the queer BDSM subculture, where alternative sexual activities deemed as low or no risk for infection were practiced. A sign of the times, a black and white checkered handkerchief to represent safer sex as a fetish appeared in hanky codes most likely in the early 1990s as a way to promote HIV/AIDS awareness and safer sex practices.

In the late 1990s the BDSM subculture reinterpreted the hanky code aesthetic through dress. Known as fetishwear or gear, military uniform-inspired dress and gladiator-inspired accessories traditionally made in black leather began appearing with an accented color associated with the hanky code. Additionally, accessories such as suspenders, shoelaces, and graphic t-shirts referencing more popular or common fetishes provided a casual approach to hanky code flagging. This new wave of fetish dressing allowed for flagging beyond the bandana, was a more direct form of sexual signaling, and provided an opportunity to openly express a sexual identity that included one’s fetishes.

While previous sartorial codes signaled queerness (with later codes also signaling sexual availability), the hanky code was the first sartorial code to simultaneously communicate queer identity, sexual availability, and sexual fetishes. In the course of its 40-plus year history the hanky code contributed to representations of queer masculinity, responded to cultural shifts in the queer zeitgeist, and evolved from a covert signifier to a sartorial declaration of queer identity, visibility, and representation.

Raul Cornier is a recent graduate of the University of Rhode Island Department of Textiles, Fashion Merchandising, and Design, with an emphasis on historic textiles and costume. His Master’s degree thesis was on the history and cultural impact of the hanky code.

The History Project is hosting our second annual flagging party and fundraiser at Jacques on Sunday, April 28. Click here for more information.

Top Related Stories

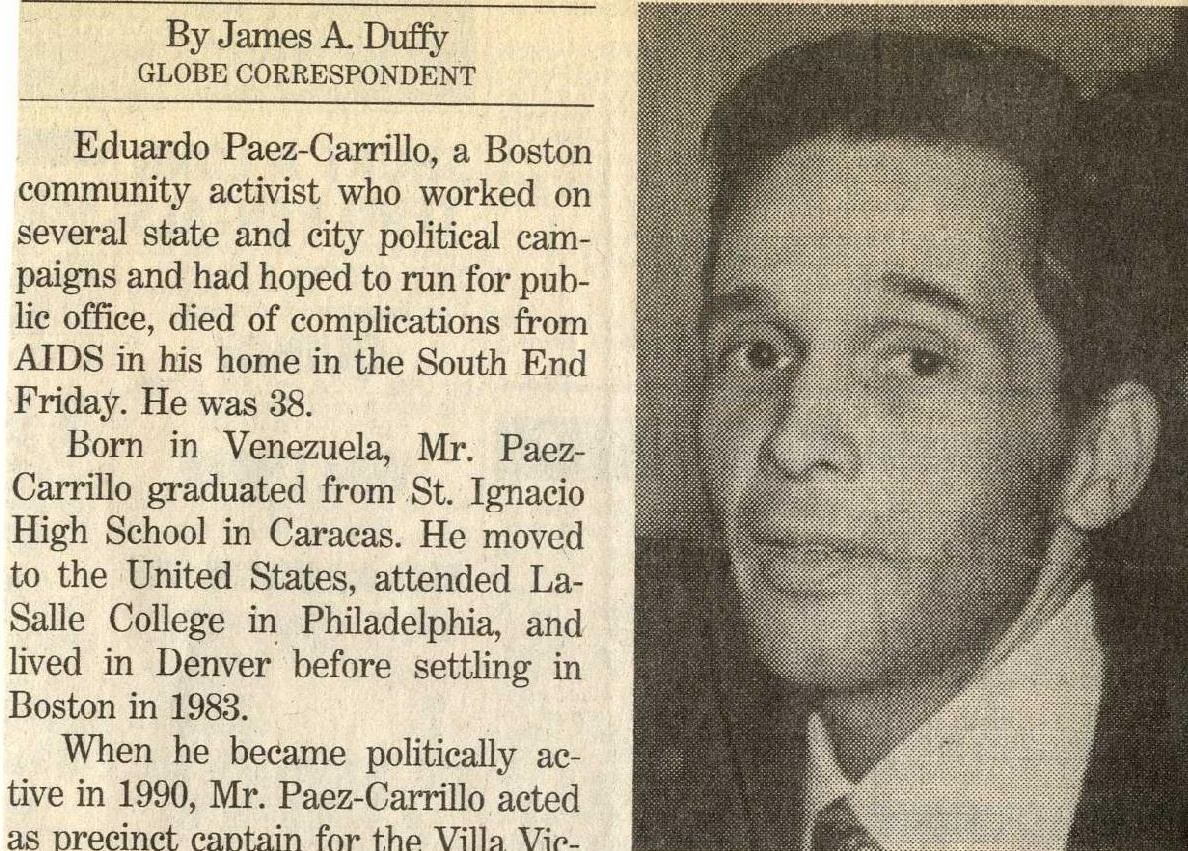

Bulletin: World AIDS Day (December 2019)

Sunday, December 1 was World AIDS Day. For those of us who lived through the years [...]

Sunday, December 1 was World AIDS Day. For those of us who lived through the years [...]

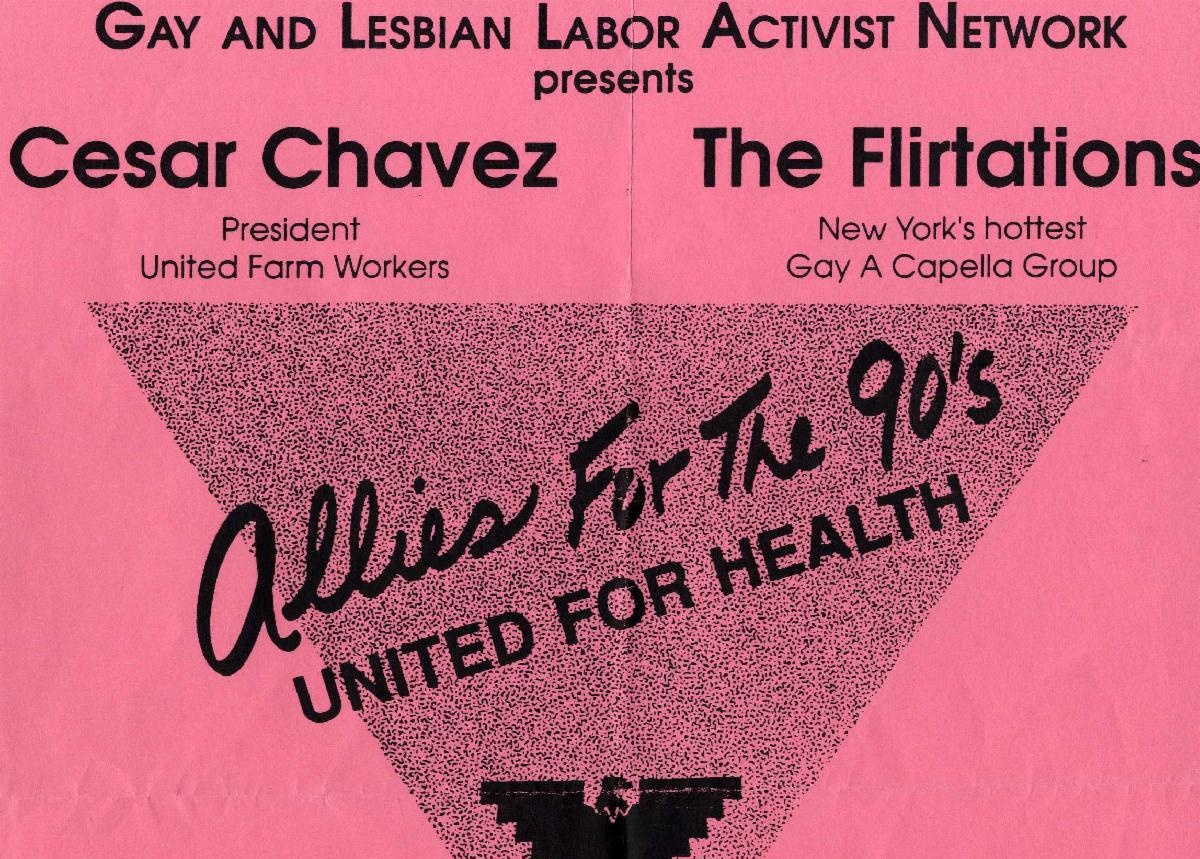

Bulletin: Gay and Lesbian Labor Activist Network (September 2019)

In honor of Labor Day, this month's focus is on the Gay and Lesbian Labor Activist [...]

In honor of Labor Day, this month's focus is on the Gay and Lesbian Labor Activist [...]

On the Cusp of Liberation: LGBTQ Voices from the 1960s

Originally published in 2015 on Mark Krone's blog Boston Queer History. In memory, each decade has [...]

Originally published in 2015 on Mark Krone's blog Boston Queer History. In memory, each decade has [...]